An Overview of The Washington Park Arboretum Master Plan

May 2001 was a momentous, defining month for the Washington Park Arboretum (WPA): after seven years of a sometimes contentious public process that led to numerous revisions, the Washington Park Arboretum Master Plan was officially approved by the City of Seattle and the UW Board of Regents.

The plan is the third in WPA’s history and is very much a living document which informs decisions made today and for the foreseeable future. It enshrines conservation, education and recreation as its motivating and primary principles and declares that “the Arboretum must maximize its value to the communities of western Washington.”

“A master plan is critical for a botanic or public garden of any size, to give it a sense of mission and purpose, and then to guide priorities to accomplish its goals,” explains Ray Larson, Curator of Living Collections at the University of Washington Botanic Gardens (UWBG).

Such a document is not a landscaping blueprint or a botanical manifesto, but answers questions like “What do we hope to accomplish with our education program and with our collections? How do we use the grounds to teach people about plants, about ecology, about the natural world?” And it lays out what is needed–in terms of staffing, facilities, budgets, fundraising and more–to attain its vision for the future.

Despite its robust vision for the future, the plan fell short in some ways due to some neighbors’ concerns that increased visitorship would dilute the Arboretum’s “neighborhood park” ambiance. As a result, some of the most ambitious facilities and buildings were nixed from draft versions of the plan, which has cramped the Arboretum’s effectiveness in some outreach and education areas.

Even so, the plan has propelled the completion of many projects, renovations and accessibility improvements, and is highly regarded by those who have worked to implement its goals. “It’s had more of an ongoing life than any master plan I’ve ever seen,” remarks Michael Shiosaki, former Director of Planning and Development with Seattle Parks and Recreation. “It really has been a guiding document that has stayed on the front burner much longer than any other plan I’ve seen.”

Arboretum Foundation Executive Director Jane Stonecipher agrees. “The public process that went into the creation of the Master Plan helped lay the foundation for a plan that’s still remarkably relevant twenty years later.”

Andy Sheffer, Director of Planning and Development with Seattle Parks and Recreation, is quick to point out that a key reason for its success was the creation of a detailed implementation plan, which was formalized in 2004. “A solid implementation plan breaks out the high-, medium- and low-priority projects and has a clear workflow for decision-making among partners,” he says. “Many plans don’t have implementation plans and suffer as a result, but the proponents of the WPA Master Plan knew it was really important and planned to make an impact.”

The working group tasked with keeping major capital projects on budget and on schedule is the Master Plan Implementation Group (MPIG), which has representation from each of WPA’s three partners: the University of Washington, the Arboretum Foundation and the City of Seattle.

Top Five

The plan’s most noteworthy and effective accomplishments include:

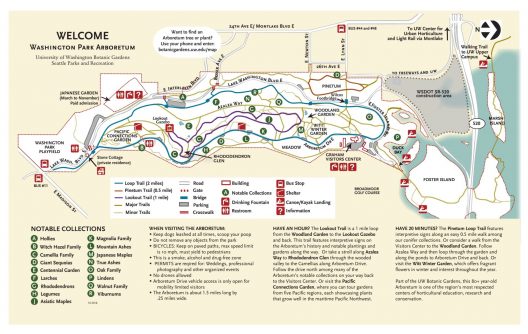

One: The charismatic Pacific Connections Garden was opened in 2008, featuring iconic plants from Australia, Chile, China, New Zealand and Cascadia–all Pacific Rim regions with temperate climates similar to Seattle’s. The multi-phased project features extensive trails, an inviting meadow, an open-air interpretive shelter, and verdant views down to the Lookout Gazebo, Arboretum valley, the University District and beyond. Thus far, preview gardens have been installed for all five regions, and forests devoted to Chile, New Zealand and Cascadia are planted. Forests representing Australia and China are still to come. Sited at the south end of the park, this 14-acre garden has helped draw in visitors through what had historically been a low-traffic entrance.

Two: The expansion of the Arboretum Loop Trail (2015-18) has “made the Arboretum feel a lot bigger. It’s been a pretty simple change in terms of the land used for it, but it’s really brought a lot more people to different areas of the park that they probably weren’t aware of or weren’t able to enjoy before,” Larson explains. Access was vastly improved with the installation of pathways to accommodate people with a range of accessibility levels, along with new entrances for bikes and pedestrians. “It’s also provided a way to enjoy the Arboretum year round, without getting your feet wet–a lot of our grounds used to be kind of squishy and inaccessible during the rainy season,” Larson notes. These thoughtful transformations have resulted in a tremendous increase in visitorship.

Three: The irrigation mainlines project (2004) was a crucial and massive infrastructure improvement. The new lines enabled the development of new gardens, such as Pacific Connections, and delivered updated capacity to many existing gardens. “It was really a complicated project–to weave the lines through the existing plant collections without doing any damage,” recalls Shiosaki. And it delivered a win-win: Arboretum Drive had to be dug up to accommodate trenches for some of the lines. Afterward, it was beautifully repaved, eliminating years of wear and tear, potholes and cracks.

Four: The restoration of Duck Bay (2004-2006), including upgrades to the Foster and Marsh Island boardwalks, resulted in improvements for accessibility, shoreline vegetation and wildlife. Decades of human use like fishing and canoeing had degraded the 1700 linear feet of shoreline, some of it in Lake Washington’s sensitive wetlands. “Previously, the lawns had run right up to the edge of the water,” Larson recalls. “While that was great for bringing people closer to water, it was really not so great for the shoreline or for encouraging birds and wildlife.” Shorelines were revegetated with native plants to provide better cover and habitat for birds, fish, amphibians and other wildlife; several viewpoints and canoe and kayak landings were established to direct those uses to appropriate areas that didn’t damage the shoreline; and the updated trails are level, flat and wide, better accommodating wheelchairs and strollers.

Five: The Seattle Japanese Garden entry did not have many facilities for staff or visitors until 2009, when the Gatehouse Village Complex changed all that. Now, visitors are greeted by an enlarged and welcoming entrance. A large meeting room offers space for public gatherings, art exhibits and workshops. And instead of portable toilets, there are restrooms. “When you increase the creature comforts and the maintenance, it becomes more of a destination for people,” Larson says.

Hindsight is 20/20

As with anything, there’s always room for improvement.

Larson and many others believe the Arboretum’s full potential is compromised by the axing of some proposed facilities during the plan’s approval process. As a result, “it hasn’t been as successful in addressing the number of facilities that would help us make it a better place for people to enjoy and learn from,” says Larson. In order to expand the Arboretum’s appeal and public engagement, many would like to see an expanded visitors’ center, education building, updated greenhouse, additional restrooms, parking, and concessions like a cafe.

Diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) were not front of mind when the Plan was being created. “The master plan recognized that a lot of people enjoy the Arboretum passively or just as an outdoor space, but it didn’t really anticipate how we are now trying to make sure it really serves the whole citizenry of the greater region, not just the neighborhood it’s in.”

“Looking back, it would have been better to cast a wider net to connect with people in a bigger geographic area and more actively engage with a greater diversity of users,” Larson remarks. “More and earlier engagement with the tribes and looking at things with more of an equity lens would have resulted in a broader range of important perspectives and views.”

UWBG has two new co-directors, Christina Owen and Josh Lawler, and Larson is very optimistic about their vision for the Arboretum’s future. “Christina is really interested in making it a more inclusive and equitable space. That’s a big priority for her.” Likewise, he sees Lawler, who holds the newly created academic director position, implementing ways to make UWBG’s research more visible, relevant and participatory for a diverse public.

“Getting people engaged and excited–that’s the hard part and the fun part. And the new leadership really gets it,” enthuses Larson.

What’s Next

In addition to the essential work to be done around equitable and inclusive community engagement, Larson estimates that there are 10 to 15 more years of project work to be accomplished before the creation of the fourth master plan. In the meantime, there are some current projects of note.

One: The Rhododendron Glen is currently undergoing a deep, multi-phased renovation. “This is going to improve the health of a deteriorated stream, add a new accessible viewpoint and greatly enhance one of the Arboretum’s most historic collections of rhododendrons and other ericaceous plants,” says Stonechiper. Again, trail enhancement is a focus: a trail spur will connect visitors to parts of the shaded, hilly Glen which is currently difficult to access.

Two: The future of Pacific Connections continues to come to fruition. The forests representing Australia, Chile and China are still to be developed. Larson also mentions that “there continues to be a circulation problem down at the south end, getting people from Azalea Way to Pacific Connections or to the Gazebo. That hill has made it a problem since the beginning of the Arboretum. We need to figure out how to get people up to Pacific Connections safely and accessibly, so that they’re not confused or lost.”

Three: Although it could not have been foreseen in the 2001 Plan, the Arboretum’s North Entry will be the largest, most complex and expensive undertaking in the Arboretum’s history. The 28-acre peninsula was a relatively undeveloped, naturalistic part of the Arboretum until in 2014, when it became a staging area for WSDOT’s extensive SR 520 Montlake Bridge Project. This temporary transformation of purpose required that all existing vegetation and visitor access be removed. WSDOT’s work is currently projected to be complete in 2029 and the site will then be returned to the Arboretum. In the meantime, Larson is hopeful that some of the land and associated mitigation funding will become available earlier so that work can begin on daylighting Arboretum Creek north of the Wilcox/Lynn Street footbridge.

This land offers a stupendous blank slate in terms of making good on the Arboretum’s DEI, conservation, education and recreation goals. Owen is already pondering its rich potential for public engagement. “Thinking about that land is just so profound for me. I’ve started asking questions around: Whose voices are at the table? How do we honor the people that were on that land first? How do we make sure that we’re reaching out and gathering those voices before any decisions get made about what happens with that land?”

Partners at the Arboretum have begun exploring these questions and more as they engage this year in the Central Park Conservancy’s Partnerships Lab. Stonecipher reflects “[The Partnerships Lab] will help us craft an updated vision for the Arboretum—with an eye towards equity and inclusion—and then help us streamline our governance model to best achieve that vision. This will be a lengthy process, and I look forward to sharing what we learn along the way.”