Rare Plants and a Changing Climate

By Maya Kahn-Abrams

Over the past five months I have been immensely privileged to work on several of Rare Care’s projects restoring our beloved native rare plants all over Washington state. From hot July afternoons helping map shimmering meadows of pink Wenatchee Mountains checkermallow (Sidalcea oregana var calva) and purple Wenatchee larkspur (Delphinium viridenscens), to epic early mornings counting baby seedlings of White Bluffs bladderpod (Physaria douglasii ssp. tuplashensis) while perched atop these white, crumbling cliffs overlooking the Columbia River, to a final month roaming the rocky inclines and rolling sub-alpine meadows of Mt. Rainier, I have had the great pleasure of spending time with a number of the most beautiful, interesting and at risks plants in our state. One aspect of this work that has been both ubiquitous and inescapable has been the pronounced and widespread signs of drought- what we humans call climate change and what plants experience as water stress. What was felt across the state as the hottest summer on record throughout the entire Pacific Northwest bioregion, has left pronounced effects and noticeable changes in the lives and greater ecologies of our beloved plant species

Seedling survival is one of the greatest challenges faced in plant restoration, especially in the arid environments of eastern Washington. The challenges faced by seedlings in years where early spring precipitation is largely absent were apparent while working to track seedling recruitment at Rare Care’s experimental direct seeding plots for White Bluffs Bladderpod (see Rare Plant Press Spring 2020 Vol 15, No.1 Seeding the Future). By counting germination success and seedling survival over multiple months in the spring, it became apparent that seedlings could not survive even a few months once rains stopped early in March. Even in experimental treatments that had successfully combined timing, technique, and microsite location to achieve good overall seed germination, long term seedling establishment remains low.

Similarly, while conducting preliminary seedling surveys of the only known population of Umtanum desert buckwheat (Eriogonum codium) at Hanford Reach, it became apparent that despite high seed production the previous year and seed germination this past winter, early spring drought was causing seedlings to turn yellow by April. Monitoring seed germination success and seedling recruitment is part of Rare Care’s ongoing work with Hanford Reach National Monument, the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Dr. Jon Baker and Dr. Britany Johnson labs at the UW School of Environmental and Forest Science, and a diverse set of stakeholders including the Washington Natural Heritage Program, US Department of Energy and the Yakama Nation Confederation of Tribes and Bands. This work aims to address a number of factors contributing to Umtanum desert buckwheat’s restricted range, declining numbers, and endangered species statues, including several studies aimed at increasing success of both seedlings and outplantings, and ultimately at stabilizing this plant’s population.

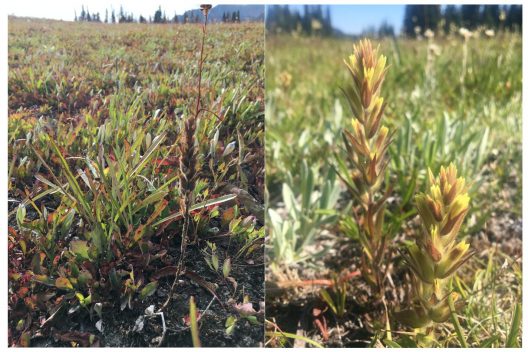

Working for Rare Care, I have both traveled widely across the state and returned to places I have previously been to check on plants. This year I was able to return to experimental outplantings of Spalding’s catchfly (Silene spaldingii) at Turnbull Wildlife Refuge near the Idaho border, and witnessed plants in full bud, ready to flower, withered and dried by the heat wave. Similar scenes of Wenatchee larkspur, dried to crisp while in full bud, trying to grow in the middle of a once perennially moist meadow, met me along the eastern slopes of the Cascades. Most heart-wrenching of all was returning to what I had known as the vibrant, rolling meadows of obscure Indian paintbrush (Castilleja cryptantha) at Mt. Rainier, to find sparse patches of plants, many of which were brown and dry, stunted while in full flower. While working in 2019 as an intern on Rare Care’s Alpine project with the National Park’s Service (see Rare Plant Press Spring/Summer 2019 Vol 14, No.1 Above the Tree Line), the sub-alpine meadows that I had witnessed as lush, moist, and lively canvases of multicolored wildflowers were now brown as heat early in the season had pushed many plants to go to seed 2-3 weeks earlier than before. Many beloved plants I visited this year, from the rare and endemic Mount Rainier lousewort (Pedicularis rainierensis), to Cotton’s milkvetch (Astragalus australis var. cottonii) in the Olympic Mountains, showed early flower onset and many dried flowers, cooked before achieving pollination and seed set.

I share these observations, in the hopes of advocating for our rare plants. As a human community, addressing the human contributions to the current climate shifts and rising global temperature being felt in ecosystems across our state, is the best way we can stand with and advocate for our plant friends. I hope that these notes from a diversity of ecosystems and a subset of rare plant species can inspire care in preserving the phenomenally beautiful biodiversity of our unique state.